Expo 67 in Montréal is often summed up in numbers: over 50 million visitors, 61 participating countries, and six months of excitement. But beyond the spectacular event, two small ideas born in Montréal quietly shaped the experience of future world expositions. Simple, yet brilliant ideas: the stamp passport, and the word “Expo” itself.

The Visa Passport: Travelling from Pavilion to Pavilion

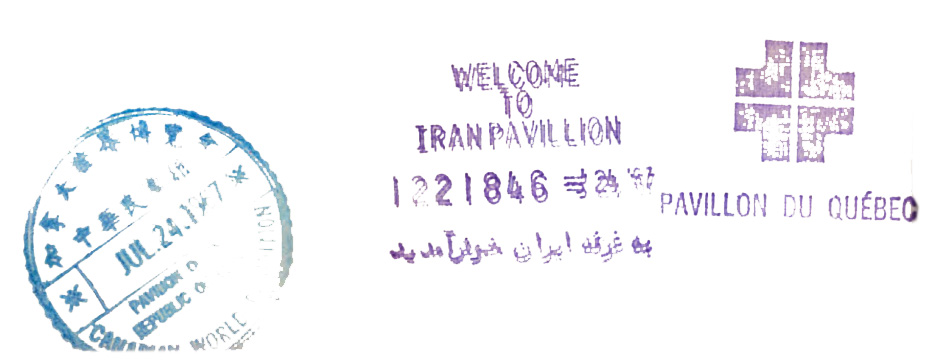

At Expo 67, the admission ticket took the form of a passport with a photo for those who chose a season pass or a 7-day pass. At each pavilion visited, guests could have a personalized stamp added — often designed by the host country itself.

This gesture quickly became a ritual. Collecting stamps and filling every page of one’s passport was a way of travelling the world without ever leaving the Expo grounds. This tangible keepsake, as symbolic as it was fun, left a lasting impression on generations of visitors. Some stamps have become true trophies among collectors.

The rarest of them all? The one from Saint Kitts–Nevis–Anguilla, stamped only on August 3, 1967, during a presence at Expo 67 that was as official as it was fleeting. With support from Air Canada — which serviced Anguilla at the time — and the approval of Commissioner General Pierre Dupuy, the Caribbean territory was able to host a one-day mini-pavilion (or rather, a kiosk) at the entrance to the Air Canada pavilion.

All day long, Miss Barbara Walton, representative of the delegation, welcomed visitors and stamped what would become the rarest visa of the entire Expo. A fleeting but very real presence — one that adds a mythical touch to the 1967 passports.

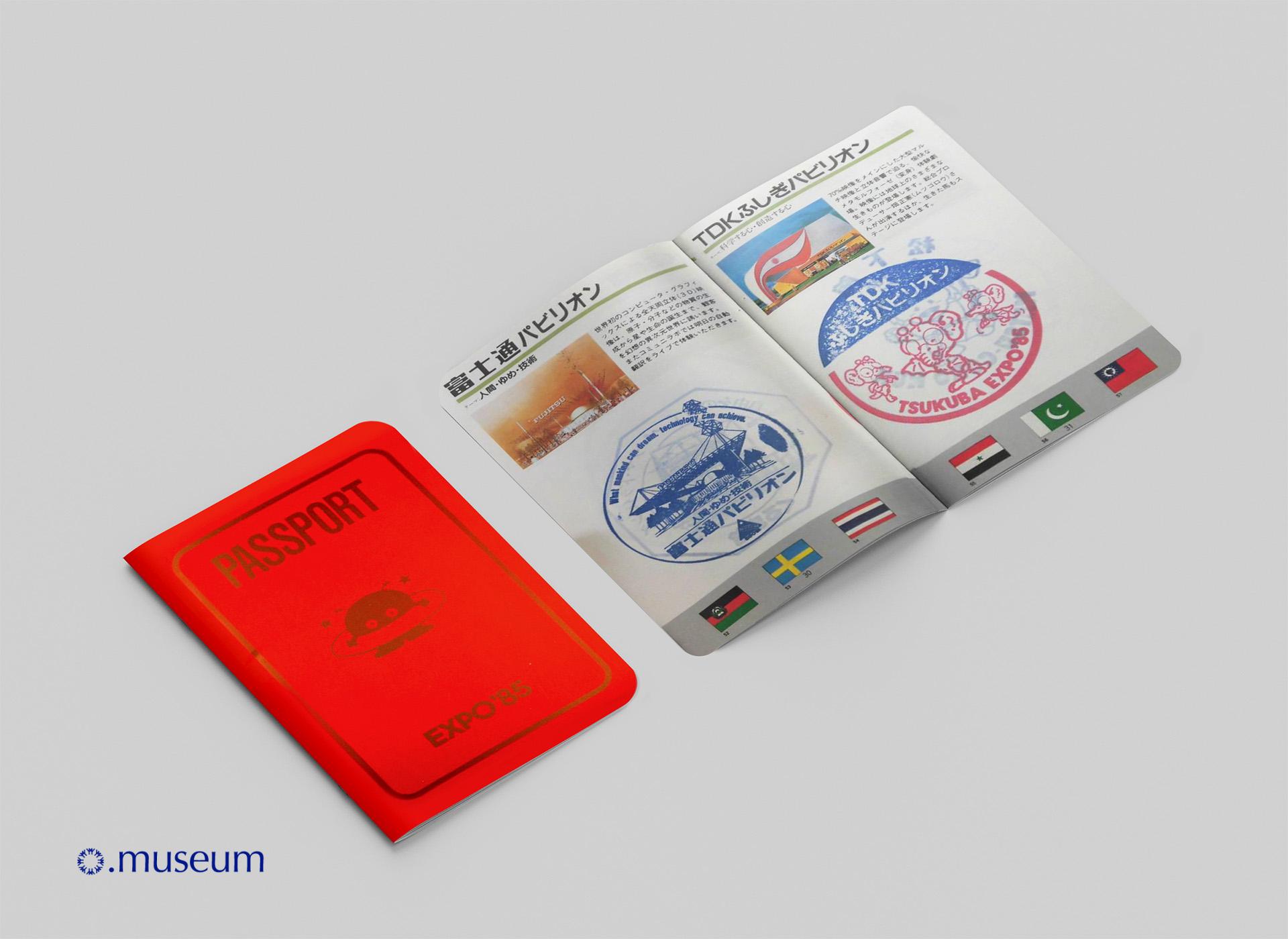

The concept caught on. Starting with Expo 70 in Osaka, and then in nearly every subsequent exposition, including the one in 2025, the stamp passport became an essential tradition. Even today, it remains a central part of the experience.

The “Expo” Brand: From Nickname to Official Name

Before Montreal, the terms “world’s fair” or “international exposition” were more commonly used — as in Brussels in 1958, sometimes nicknamed “Expo 58” by the media, though never officially. The Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) continued to use very formal terminology.

It was in Montreal, with the 1967 Universal and International Exhibition, that the word “Expo” became an official, fully embraced title. Expo 67 — one short word and a number, a graphic punch: easy to remember and distinctly modern.

This choice was anything but trivial — and far from unanimously welcomed.

From the very first promotional campaigns, the word “Expo” stirred some resistance, particularly among English-speaking Canadians. Some circles preferred the full term “Universal and International Exhibition” to align with official conventions, or simply “World’s Fair.” Others felt “Expo” sounded too French — and meaningless in English.

"I waged a three-year battle with the Gazette and the Montréal Star who fought hard to get Expo to change its name to Montréal's World Fair. For two of those years we were in direct conflict with the New York World's Fair, still the Montréal English speaking journalists fought Expo tooth and nail, saying that Expo sounded like a new brand of cigarette, that Expo did not convey the significance of an Exhibition, etc."

Yves Jasmin, private interview quoted on expo67.ncf.ca

But French speakers, especially Pierre Dupuy’s team, with him serving as Commissioner General of Expo, defended the use of a simple, catchy, neutral, and identity-affirming word. “Expo” quickly became an effective linguistic compromise, a term everyone could embrace. It was adopted in visual branding, advertising, tickets, transportation, and more.

Given its success, the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka officially adopted the shortened name “Expo 70,” with the approval of the BIE. While the long form remained official for protocol purposes, no subsequent exposition returned to the older terminology in everyday communication. “Expo” became a global brand, born, or at least cemented, in Montréal.

It just goes to show that a small communications decision can change language, and even history.