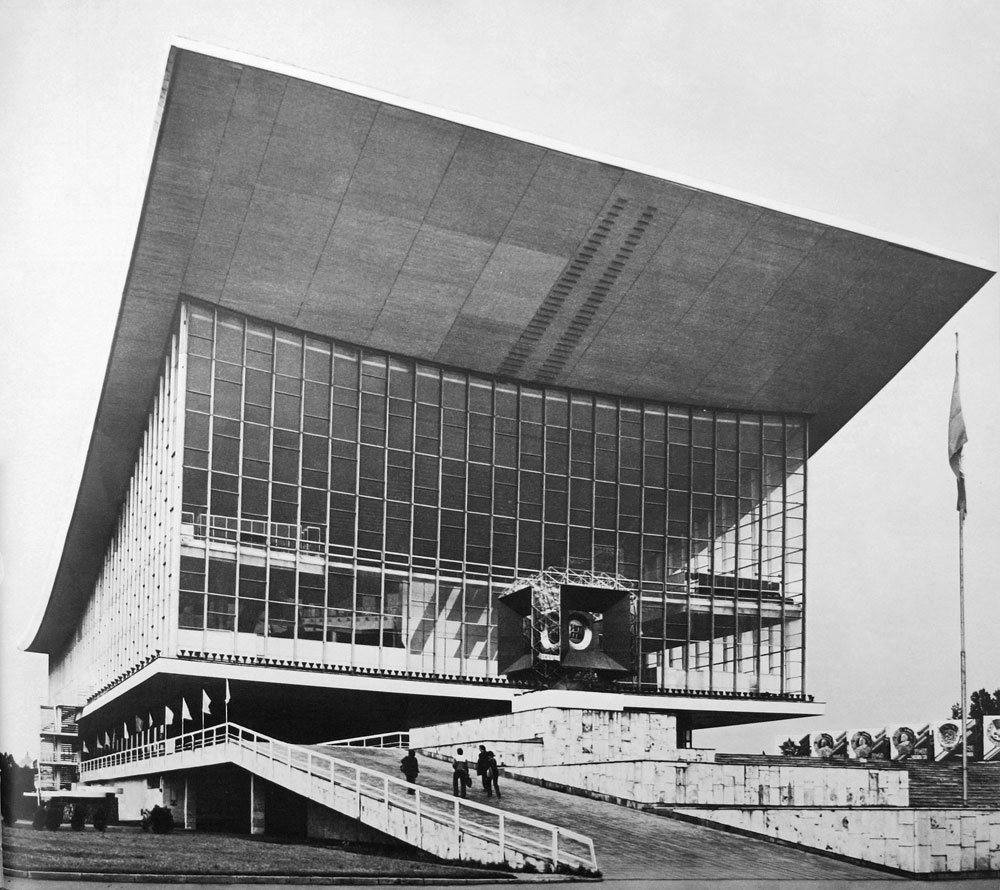

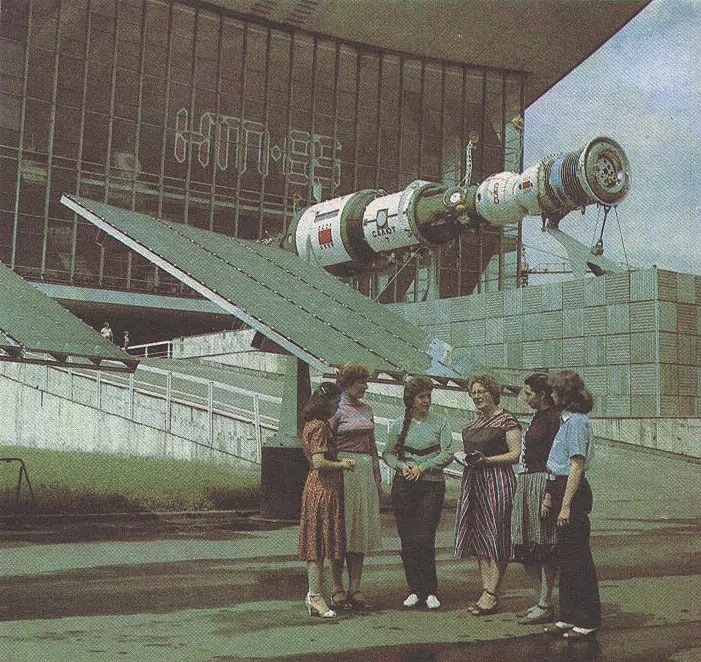

The USSR Pavilion captures the imagination with its imposing stature and futuristic design. A striking symbol of socialist progress, it stands as a manifesto of steel and glass, projecting the Soviet Union’s power in direct contrast to its American rival. Its skyward-reaching architecture evokes space exploration and technological dominance during the height of the Cold War. More than 12 million visitors passed through its doors, making it one of the most visited pavilions at the fair, even surpassing the American dome.But its story didn’t end on the shores of the St. Lawrence. After the event, the entire structure was dismantled and shipped to Moscow, where it was carefully rebuilt. This relocation stands as a remarkable example of active preservation of a World Expo pavilion, repurposed in service of Soviet power and now situated in a constantly shifting geopolitical context.

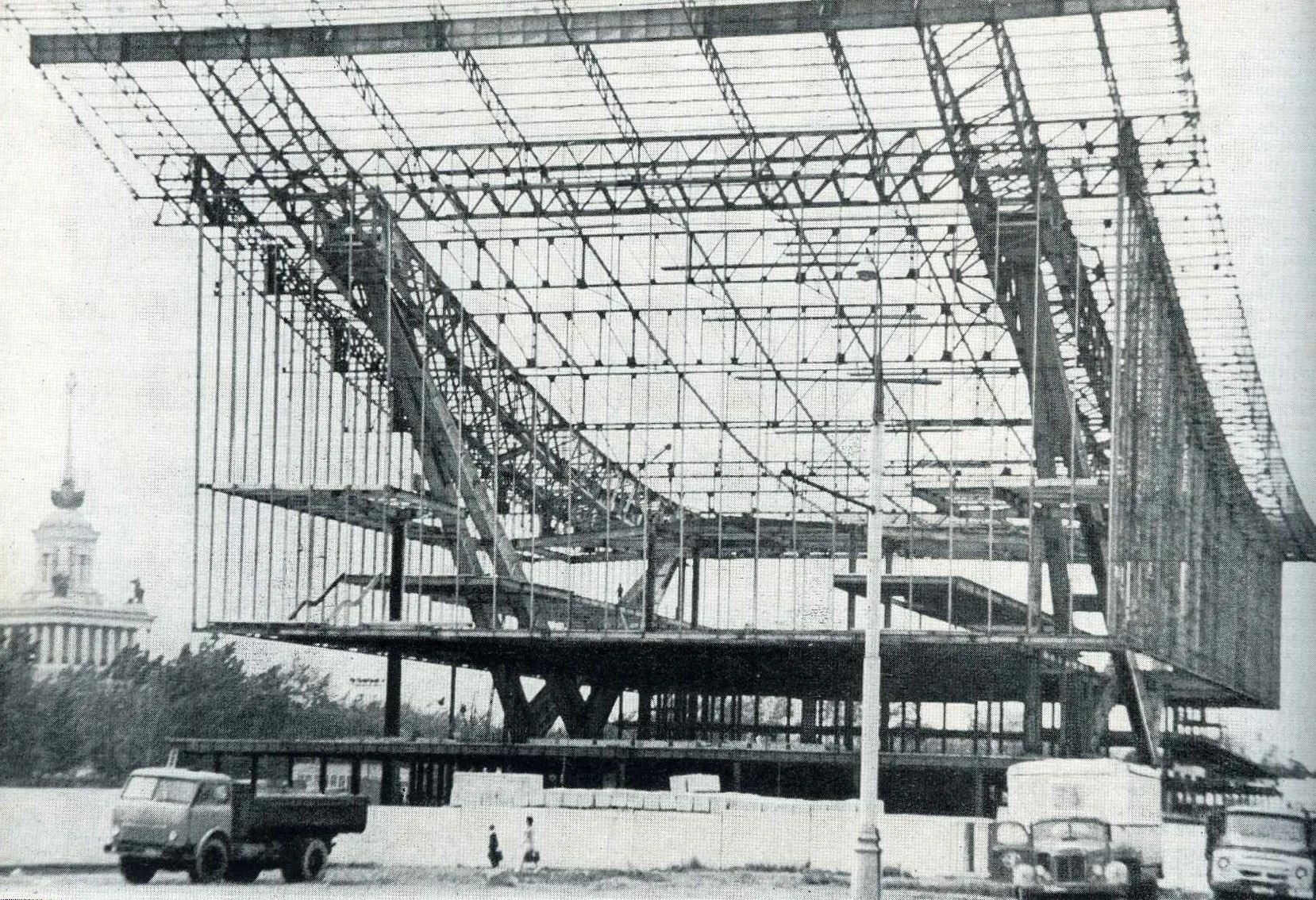

The pavilion was designed by Mikhail Posokhin, architect of the Kremlin and author of the Kremlin State Palace (1961), with the assistance of Ashot Mndoyants, Boris Tkhor, and engineer A. Kondratiev. Its architectural language blends monumentality, sharp lines, and symbolic effects. The building’s tapered form, dominated by a metallic canopy soaring skyward, evokes both space exploration and the ideology of progress. This feature is said to have been inspired by an original idea from Konstantin Melnikov, a leading figure of the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s.

“Since we had no knowledge of what the other pavilions would look like, we decided to express in our pavilion’s architecture a sense of dynamism, a drive to move forward, a sense of flight.”

Mikhaïl Posokhine 1

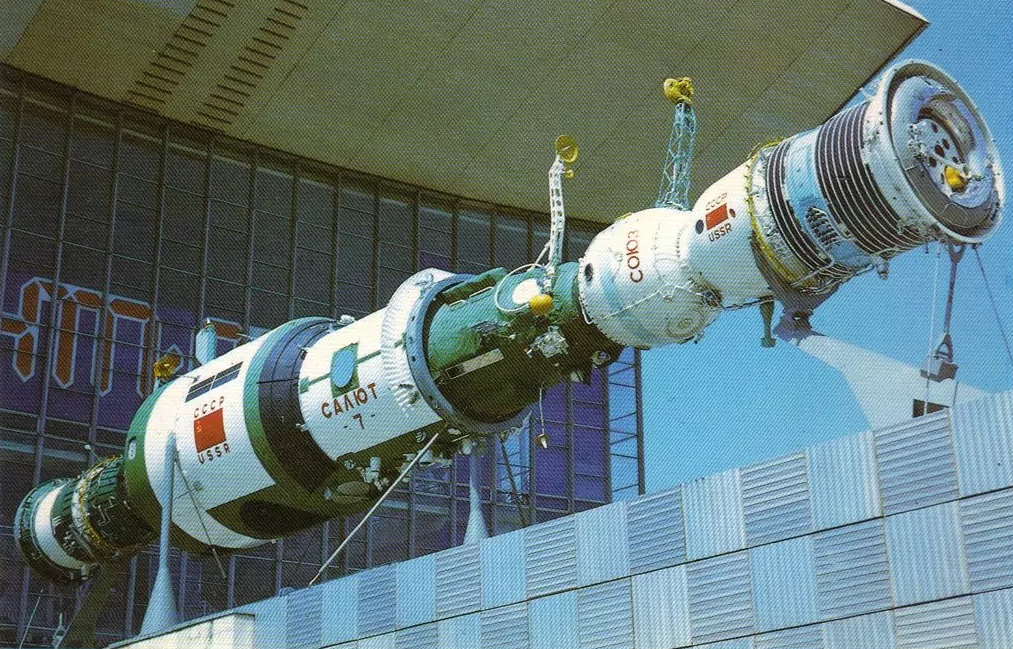

Inside, the pavilion featured three thematic levels: on the lower floor, marine worlds and energy; in the middle, industry, agriculture, and production technologies; at the top, space exploration, showcased through satellites, simulators, lunar imagery, and a model of the Tu-144. Together, they presented an ambitious USSR, firmly oriented toward the future.

Rudolf Kliks, responsible for artistic direction, is portrayed in some accounts as an intriguing figure, possibly linked to Soviet trade circles in New York, with a background that may have intersected with industrial espionage. The design and development of the Soviet pavilion were the subject of an in-depth investigation by French historian Fabien Bellat 2, a specialist in Soviet architecture. Bellat was interviewed by Le Devoir in 2012 3. In the article, Bellat details Posokhin’s role and Melnikov’s influence on the pavilion’s design. He also describes the technological rivalry between the blocs as a driving force behind the pavilion’s scenography and highlights the logistical absurdity of shipping the building — “placed in a boat twice” — back to Moscow.

One of the most surprising aspects highlighted by historian Fabien Bellat is the exceptional cost of the Soviet pavilion, estimated at 15 million dollars, far exceeding the 9 million invested in the American dome. Several components were manufactured by the Italian firm Feal, based in Lyon, although most of the materials were Soviet-made. This hybrid strategy, combined with the cost of dismantling and shipping the structure twice by sea to Moscow, significantly increased an already hefty bill. Despite being a temporary installation, the pavilion was conceived from the outset as a long-term asset.

A Second Life in Moscow

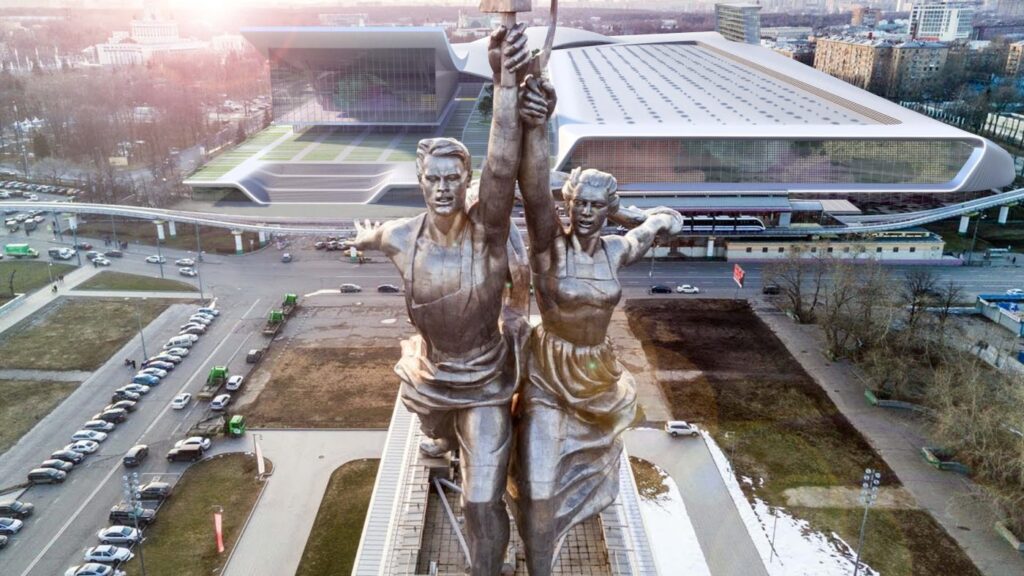

Transported by ship, temporarily stored, then reassembled between 1968 and 1975 at VDNKh Park in Moscow, a vast permanent exhibition site, the pavilion was renamed “Pavilion 70,” then “Pavilion Moscow.” It initially served as a temporary exhibition space in support of Soviet propaganda.

In the 1990s, following the collapse of the USSR, the building was officially renamed “Pavilion Moscow” and converted into an informal shopping centre. Its interior was divided into small stalls and kiosks selling clothing, electronics, mobile phones, and other goods. This indoor market became a popular spot, frequented daily by Muscovites. On occasion, the pavilion also hosted cat shows, a striking contrast with its original role as a showcase of Soviet ideology and technology.

Other Expo 67 buildings were also relocated, including the Czechoslovak pavilion, which was reinstalled in Newfoundland.

A Pavilion in Transition: Controversy Over a Restructuring

Long overlooked, the pavilion regained significant visibility in 2023 when it was used as the venue for the patriotic forum-exhibition “Russia,” held at the VDNKh site in Moscow amid the war in Ukraine and heightened ideological mobilisation.This grand-scale event, officially opened by Vladimir Putin on November 4, National Unity Day, featured more than 130 exhibitions showcasing Russia’s achievements in every field, from nuclear energy to digital innovation. It made use of VDNKh’s most iconic pavilions, including the former USSR pavilion from Expo 67, which was transformed into an interactive space glorifying national accomplishments.

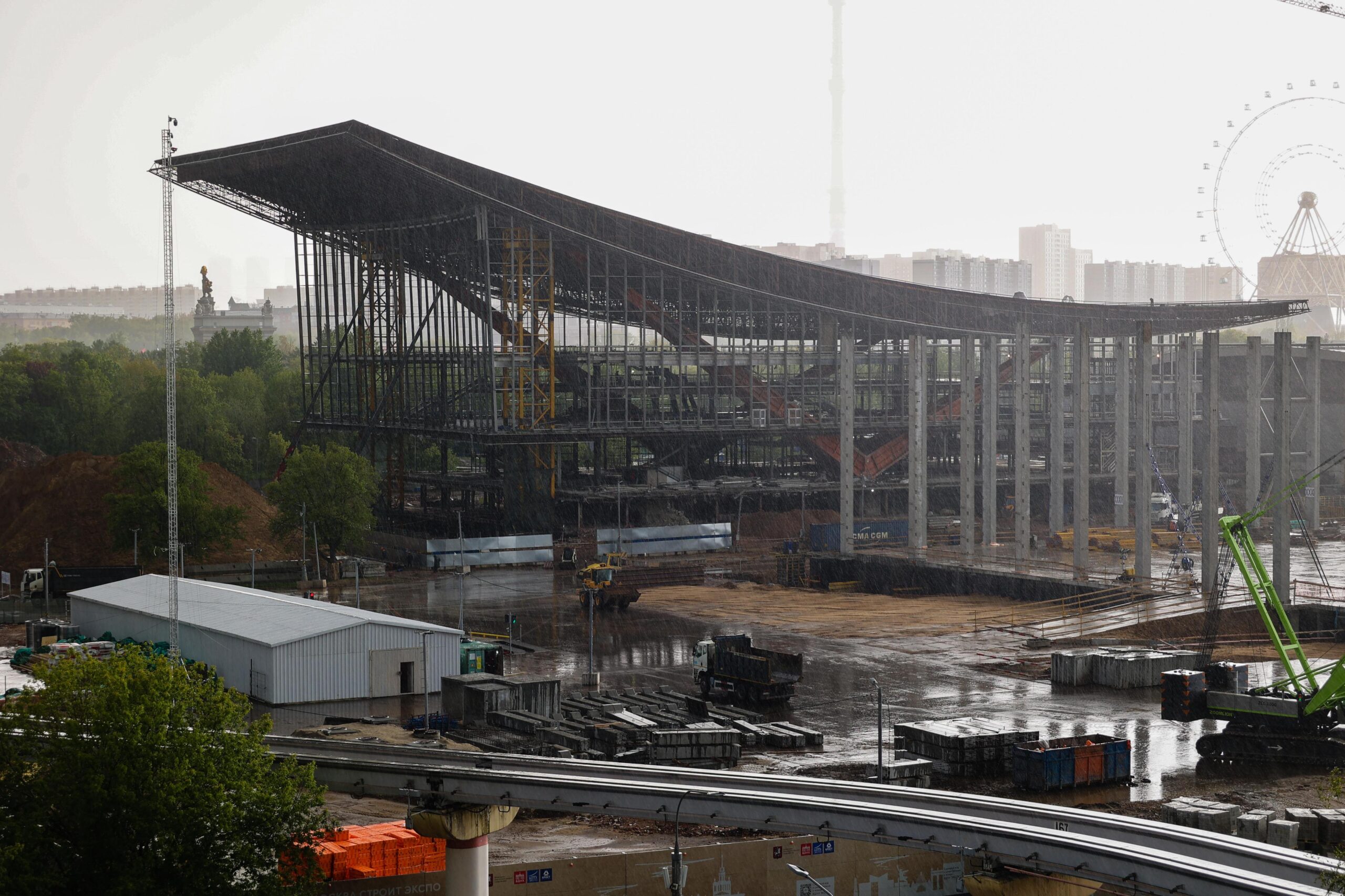

After several failed renovation attempts around 2020, the pavilion was finally partially dismantled in May 2025 as part of the “VDNKh-Expo” project, a large-scale initiative to redevelop the site's various pavilions into a multifunctional complex.

The gallery below shows the original 2020 design, now revised.

According to Russian media outlets MSK1.ru and MyDecor.ru, the work includes the complete removal of all glazing, stripping of the metal framework, demolition of the stylobate staircases, and full clearing of the interior. The building is surrounded by fencing and placed under video surveillance. Although officially described by authorities as a “reconstruction,” the intervention is widely viewed by critics as a disguised partial demolition.

The redeveloped VDNKh-Expo complex will bring together Pavilions 70 (“Moscow”) and 75, along with a new building connected by a covered gallery, for a total area of approximately 240,000 square metres. With a budget of 38.6 billion rubles, the project will include a 2,500-seat auditorium, several modular exhibition halls, dining areas, and an underground parking facility. Pavilion 70 will be transformed into a concert and convention centre, while Pavilion 75 will be upgraded to host large-scale events of up to 15,000 people.

The gallery below shows an architectural rendering of the 2025 project. The overall plan aims to transform this section of VDNKh into a major cultural and event hub.

Voices are being raised against the redevelopment of this iconic pavilion, a move considered especially problematic given the uncertainty surrounding its heritage protection status. This shift marks a clear break from earlier conservation efforts. Long preserved in its original Soviet form, the pavilion is now undergoing a thorough transformation to serve a new purpose.

This repurposing is part of a broader strategy to revamp the VDNKh site and reposition it as a showcase for the current regime. Beyond the architectural implications, the project reflects a deeper question about how Soviet heritage is treated in today’s Russian public space.

A Major Surviving Landmark of Expo 67

Few people realize that the Soviet pavilion from Expo 67 still stands in Moscow, far from the shores of the St. Lawrence. Its post-Expo journey shows how some traces of 1967 have continued to carry the memory of the event far beyond Canada, in political and urban contexts that have changed dramatically.

While most pavilions were dismantled or repurposed, a few remain. Some are still here in Montreal, while this one, thousands of kilometres away, continues to exist as a silent witness to a time of confrontation and spectacle between two worlds. A fragment of Montreal’s history now quietly rests in a Moscow exhibition park undergoing transformation.

- Podgorskaya, N. O. Pavilions of the USSR at International Exhibitions. Moscow, 2013. pp. 191–212. 224 pp. ISBN 978-5-905494-10-9.[↩]

- Bellat, Fabien. CCCP’67: un monument à la guerre froide. Paris: Éditions B2, 2018. Patrimoine series. ISBN: 9782365090889[↩]

- Doyon, Frédérique. “La saga du pavillon russe d’Expo 67 – Enquête sur un symbole de la guerre froide,” Le Devoir, August 27, 2012[↩]

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Thank you for the efforts on this site. Expo 67 was fantastic, Everyone who helped make it happen can be proud of their work, efforts, creativity, imagination, realisation. I spent the summer there. I saw so much of the world.It impacted my whole life.