To evoke Expo 67 in Montreal or Expo 92 in Seville is to revisit two exceptional moments, twenty-five years apart yet united by a shared ambition: to leave a lasting mark on their generation through strong symbolism, bold urban reinvention, and a common sense of playful legacy. Although rooted in different historical contexts, these two world expositions reflect one another in their shared desire to shape the future while leaving a deep imprint on the collective imagination.

A powerful visual identity

Expo 67 and Expo 92 both gave rise to symbols that became iconic. In Montreal, the logo designed by Julien Hébert, featuring a circle of stylized human figures, conveyed an ideal of global unity during a time of geopolitical tension. This simple, universal image came to embody the enduring humanist spirit of Expo 67.

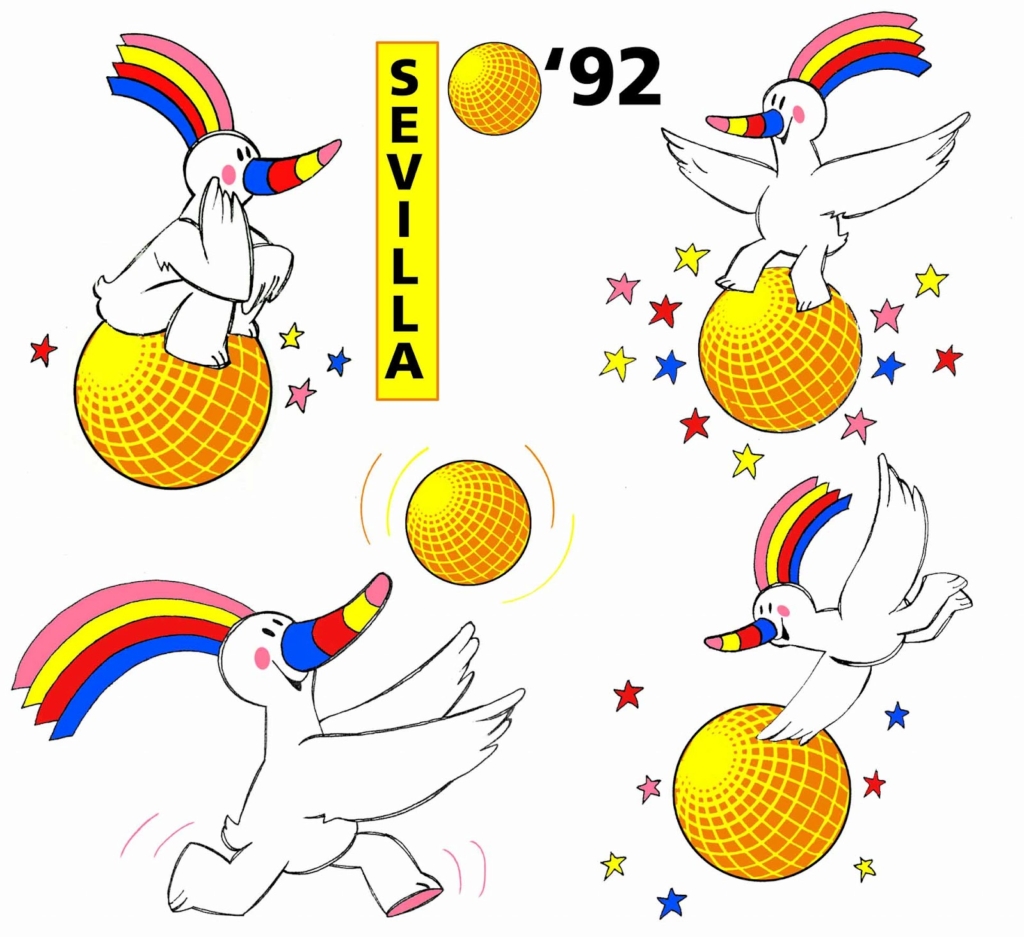

In the same way, Curro, the mascot of Expo 92 in Seville, went beyond its promotional role to become a true pop culture phenomenon. With its rainbow beak and cheerful silhouette, Curro came to symbolize the optimism of early 1990s Spain, leaving a deep imprint on the collective memory and helping to establish Expo 92 as a moment of cultural renewal following a period of intense political and social transformation in the country.

Reshaping the city on an archipelago born of imagination

Both expositions also shared a strong desire to permanently reshape their urban environments. In Montreal, Expo 67 radically transformed the landscape through the redevelopment of Île Sainte-Hélène and the complete creation of Île Notre-Dame, connected by bridges, walkways, and the new Metro Line 4 (yellow line). The event stood as a symbol of architectural and urban innovation.

Seville underwent an equally dramatic transformation by redeveloping the once-marginalized Isla de la Cartuja into a vibrant hub of modernity. The Alamillo Bridge, designed by Santiago Calatrava, and the Barqueta Bridge, created by Juan J. Arenas and Marcos J. Pantaleón, quickly became iconic symbols of the city’s bold vision for reinvention. In both cases, the newly created or reimagined spaces reflect a shared ambition: to offer visitors a tangible vision of an inspiring and functional future.

A spectacular experience in motion

Beyond urban planning, these global gatherings aimed to be true planetary showcases of progress. They embodied a dynamic and immersive experience, seeking to create an exhibition in motion by multiplying vantage points and introducing innovative means of transportation across the site.

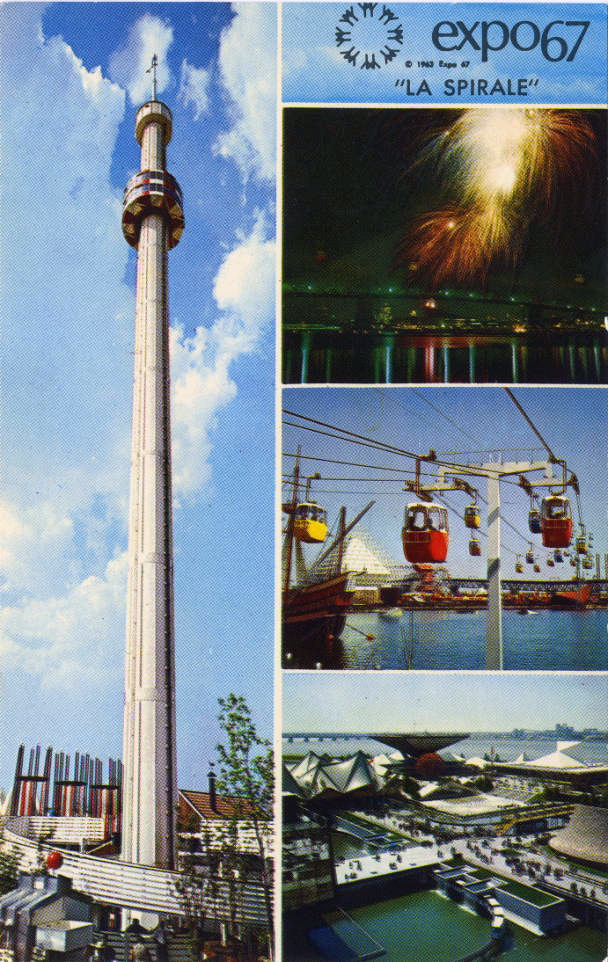

Both expositions featured iconic panoramic towers. In Montreal, La Spirale, a 92-metre tower, offered visitors a spectacular 360-degree view of Île Sainte-Hélène, Île Notre-Dame, and the Saint Lawrence River. In Seville, the 92-metre Torre Banesto provided an equally striking perspective over the Expo 92 site and the Guadalquivir River, reinforcing the central role of verticality in the scenography of both events. Sharing a similar fate, both towers are now closed to the public.

Transportation was another major highlight of both expositions. In Montreal, the Expo Express, a high-capacity automated train, efficiently connected the various sectors of the site. In Seville, an elevated monorail, six metres above ground, served three key stations (North, East and South), facilitating movement between international pavilions and major thematic areas. In both cases, these systems reflected a shared commitment to functional innovation and fluidity in the visitor experience.

Cable cars also played a practical and symbolic role. Montreal’s Minirail, a true aerial attraction, allowed visitors to glide above and through the pavilions, offering a unique vantage point to appreciate the site as a whole. When it was dismantled in 2022, many voices called for the preservation of this iconic structure. In Seville, a cable car crossed the Guadalquivir River, directly linking the historic city with the Expo site, reinforcing the connection between urban heritage and futuristic vision.

Theme parks as a living legacy

Finally, Expo 67 and Expo 92 also share a legacy in how the expo experience was extended through amusement parks, originally conceived to carry forward their popular appeal. In Montreal, La Ronde, developed on Île Sainte-Hélène, remains a major urban entertainment venue to this day, despite ongoing debates over Six Flags’ management, particularly regarding maintenance and respect for the site’s heritage.

Seville followed a similar path, though slightly later, with Isla Mágica, which opened in 1997 on part of the original Expo 92 site. Although the park has faced financial challenges and criticism over its management decisions, it has helped preserve certain elements of the original exposition. In both cities, these parks reflect a shared desire to keep alive the spirit of discovery and conviviality that defines world’s fairs.

Le pavillon manquant, le pavillon marquant

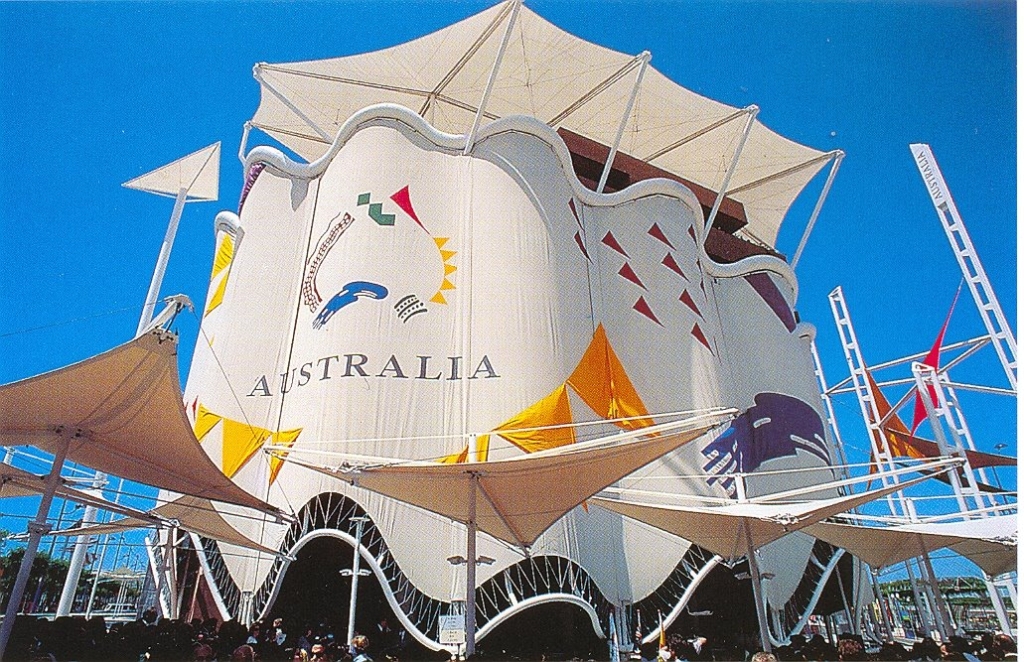

At Expo 92 in Seville, Canada stood out with one of the site’s most popular pavilions. Designed by Canadian-Chinese architect Bing Thom, the building drew long lines thanks to its 500-seat IMAX theatre, where a breathtaking immersive film took viewers on a journey through Canada’s geographic and social landscape.

The experience continued in an exhibition area divided between British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, each showcasing their landscapes, cultures and innovations. This pavilion, a symbol of a modern and open Canada, still exists today: it now houses the Escuela de Organización Industrial (EOI Andalucía), within the Cartuja 93 technology park.

In Montreal, a quarter of a century earlier, Expo 67 took place without Spain. After heavily investing in the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the Franco regime withdrew from the Montreal project for budgetary reasons. This absence was considered a personal failure by commissioner Pierre Dupuy 1.

Spain would eventually make an appearance in 1969, as part of Man and His World, the thematic and partial continuation of Expo 67 initiated by Mayor Jean Drapeau.

The dual apex of a historical cycle

Expo 67 and Expo 92 stand out not only for their scale and symbolic impact, but also because they represent the two peaks of a historical cycle: they are the two largest world expositions of the second half of the 20th century. Despite their differing contexts, both reflect a shared ambition — to represent their era, unite their nation around a collective project, and offer the world an image of modernity, openness, and pride.

In 1967, Canada celebrated the centennial of Confederation and chose to express its unity through a gesture turned outward, asserting its cultural diversity with a distinctly optimistic spirit. Amid the post-war boom years, Expo 67 condensed the era’s belief that technological progress and social innovation went hand in hand. It captured a moment of economic expansion and relative geopolitical stability, when nations still believed in the power of cultural diplomacy to build a shared future. Islands were built, dreams were cast in concrete, glass and plastic, and the idea of a united, bold, and fraternal world was projected for all to see.

Twenty-five years later, Expo 92 took place at a different crossroads. As Europe was preparing for political unification and Spain sought to assert its renewed modernity, the Seville exposition marked both the height of a spectacular model and the symbolic conclusion of Spain’s democratic transition. The country staged two major global events — Expo 92 and the Barcelona Olympic Games — to affirm its place on the international stage. Expo 92 also marked the end of an era of sustained growth and massive public investment, just before the onset of neoliberal globalization, austerity policies, and a deep rethinking of the state’s role in culture and land use planning.

Expo 92 unfolded as the post-Cold War order was unraveling. The collapse of the Eastern Bloc was redrawing Europe’s political map, and several pavilions reflected this shift. Germany, reunified in 1990, had already committed to participating under a single flag. The joint pavilion became a clear statement of unity in a Europe undergoing profound reconfiguration.

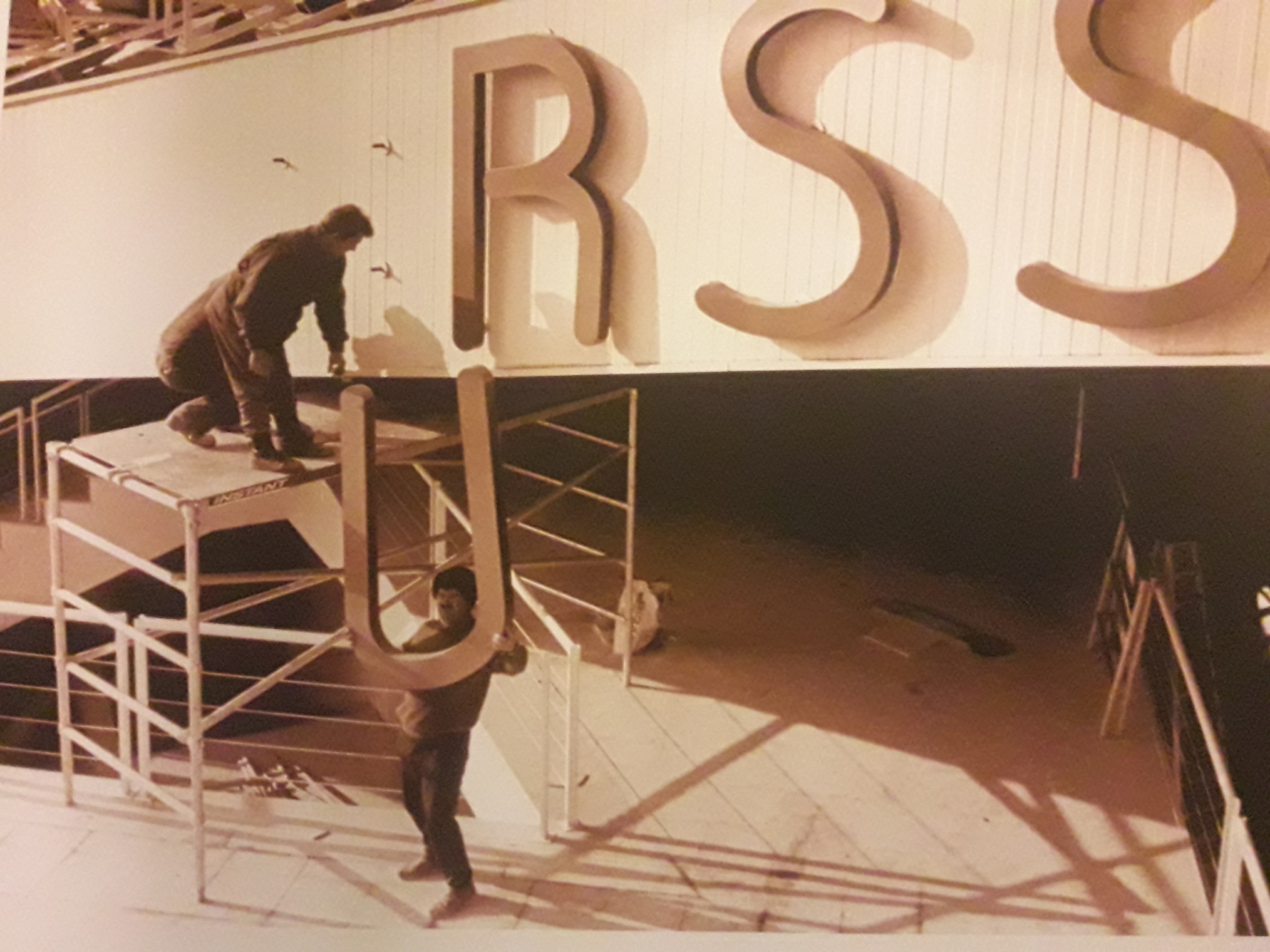

Other nations arrived in the midst of transition. Czechoslovakia was still officially united, though it was widely understood that separation was imminent. The Expo acted as a temporary showcase for a country nearing its end. Russia, for its part, succeeded the USSR with a pavilion marked by both rupture and uncertainty. Its presence reflected the hesitation of a state in the midst of reconstruction, navigating a deep transitional period.

Tensions were even more palpable in the case of Yugoslavia, then gripped by civil war. As conflict ravaged the Balkans, the presence of the Yugoslav pavilion became highly sensitive. Under pressure, Expo officials demanded the removal of the national flag, a symbol deemed too politically charged amid the country’s violent disintegration. The pavilion continued its activities in a heavy atmosphere — a silent witness to a nation breaking apart in real time.

This was not the first time a world exposition had to navigate diplomatic tensions. In 1967, Kuwait was the only country to withdraw prematurely from Expo 67, in protest of Canada’s support for Israel during the Six-Day War in the Middle East.

More than just a festive event, Expo 92, almost in spite of itself, captured the fault lines of a world on the verge of major upheaval.

After 1992, no world exposition would ever reach the same scale or intensity. Expo 2000 in Hanover, despite its forward-looking ecological message and the symbolic shift into a new millennium, was widely perceived as a partial failure, hampered by lower-than-expected attendance and a significant deficit. The following editions — Aichi 2005, Shanghai 2010, Milan 2015 — took place in more fragmented, uncertain contexts, where the Expo became one urban development tool among others, refocused on targeted issues like the environment or technology.

With Expo 2020 in Dubai, postponed to 2021 due to the global pandemic, there was a clear attempt to bring back the spectacle. Petro-dollars flowed to make it happen, but the world had changed. It had become more fragmented, more digital, more skeptical of grand narratives. The Expo regained a certain shine, but no longer quite the same soul.

In that sense, Expo 67 and Expo 92 seem to mark the end of an era — a time when world expositions still served as a framework for a collective ambition, both cultural, political and urban. They were platforms for national projection, but also spaces where countries observed one another, engaged in dialogue, and attempted to imagine a shared future.

These moments now stand as landmarks. They remind us of a time when architecture, diplomacy and innovation could still converge into a shared narrative. The belief that it was possible to build worlds shaped by ideals. The belief that we could think together, in the open air. This kind of promise never fully disappears. It lingers, somewhere, in the memory of places.

- Expo 67. Quels pays seront à Montréal ?, La Roche, Roger, May 11, 2017, MEM – Centre des mémoires montréalaises[↩]